Dynamics of Shape

1.Dynamics in architecture

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, dynamics became an important topic of intellectual speculation. Futurists, with their love for speed, noise, machines, reveiled how a city functions as a complex mechanism. How it moves and vibrates constantly, each component, each gear, being another machine. Paintings, sculptures, poems and buildings cease to represent a static moment. The mechanism that generates the work, reflects its inner dynamical structures. The creative forces are expressed in their constant moving essence.

The domestic space in those years is not a rigid, solid, static following of walls and floors anymore: moveable interiors mutate the rooms of the revolutionary “La Maison de Verre” by Pierre Chareau in Paris. In the same years, facades become organically “alive” under the influence of Art-Nouveau Architects such as Horta, Guimard and Gaudi. Structures inspired by nature are composed following geometric constructions of generatrix curves moving over one or several lines known as directrices. Hyperbolic paraboloids, hyperboloids, helicoids and cones were frequently used by Gaudì who adopted them from nature, analyzing rushes, reeds and bones. The same research was developed in the groundbreaking work of architect, scientist and composer Iannis Xenakis. He applied acoustic technologies, integrating musical ratios with complex ruled surfaces, for the Philips Pavilion shown at the Expo ‘58 in Brussels: a shell composed of nine hyperbolic paraboloids which design was inspired by the dynamics of his early musical composition Metastaseis.

These mathematical minimal surfaces, already theoretically introduced by the mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange in 1772, were solved geometrically exactly in these years. Recent discovery by Celso José da Costa in 1982 renewed the interest in the geometrical properties of the embedded minimal surfaces. His intuitions were developed and visualized a few years later by Eric W. Weisstein thanks to the progress of computer graphics which allowed to solve more and more complex parametric formulas. CAD technology enabled experimenting the application of such surfaces, recently explored because of the optimized structural efficiency thanks to their constant mean curvature.

The improvements of CAD softwares and hardwares nowadays enriches our design possibilities combining infinitive sets of information. Computational Design seems to be the current key to explore and reproduce the complexity and the beauty of Nature. Sometimes results are just mimetic imitations of Nature. Sometimes they disclose how Nature responds to certain conditions, mutating the inner composition and physical structure of living beings adapting them to selected impulses. Two research trends are currently exploring this logic: one deploys artificial intelligence codifying and elaborating the information, generating codes which ultimately are translated mechanically into preconfigured reactions. The other directly links impulse and reaction, eliminating intermediary components if not directly integrated in the material. The bio-chemical composition, physical properties and natural reactions of a material are analyzed and subsequently translated into a controlled application of the various mutations displayed.

- Mechanically Reactive membranes

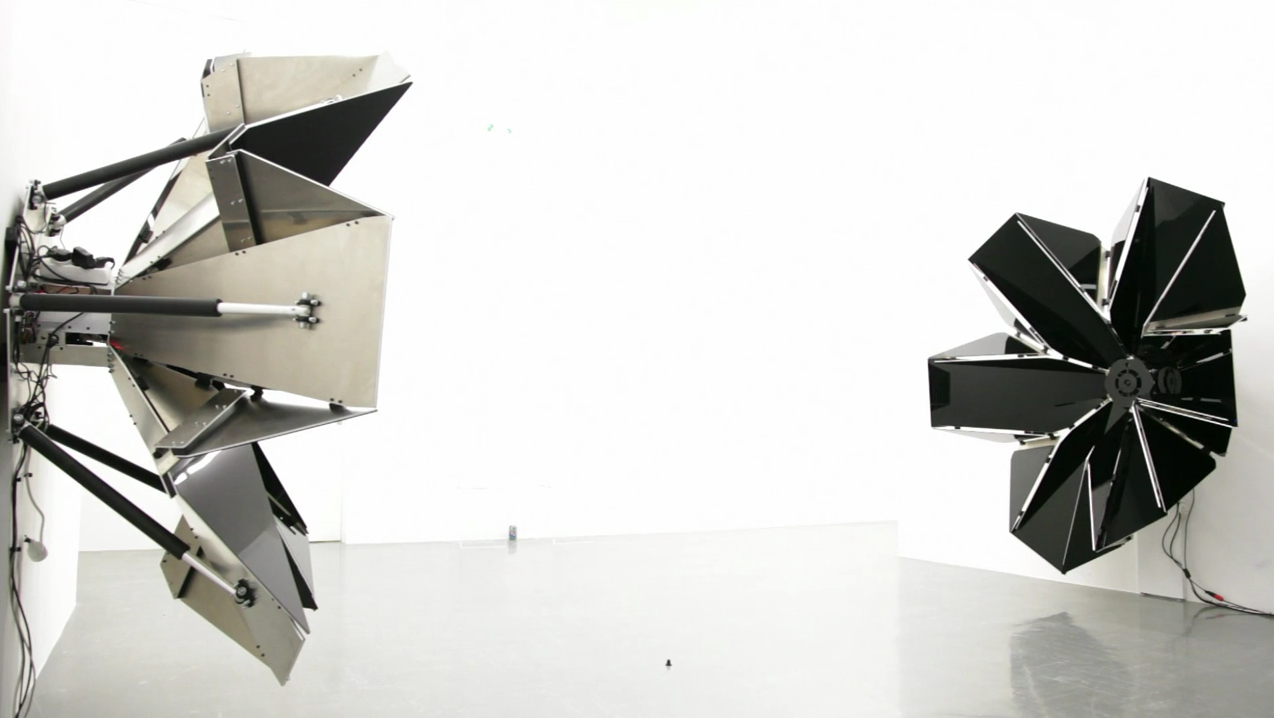

Mainly used for art installations, this type of performative membranes frequently creates a playful interaction with the visitor. Most kinetic membranes are based on the principle of movement detection: sensors register body movement and pass the received information to a computer that generates a robotic, electronic or electromechanic reaction. David Letellier’s Versus installation creates interaction between mechanical sculptures through sound emission. The work, sponsored by INSA foundation Lyon, consists of two kinetic sculptures placed face to face. Each sculpture is controlled by a specific program. At the center of each corolla, a loudspeaker and a microphone allow to play and record sounds. At regular intervals, each sculpture produces a sound, simultaneously recorded and analyzed by the opposite sculpture, which then moves according to the frequencies of this sound.

HypoSurface, a project developed by dECOi Architects and MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is a totally dynamic screen surface which physically moves according to any input (sound, movement, internet feed, etc.) that can be linked to any output (logos, patterns, text, etc.).

In order to create a space reactive to brain activity, Guvenc Ozel, in collaboration with designer Alexander Karaivanov and media artists Jona Hoier and Peter Innerhofer, hacked and reprogrammed a commercially available device able to measure concentration levels and blinking. The team scripted a program translating the data thresholds into motion and created the pavilion Celebral Hut with modular membranes expanding according to the visitor’s cerebral activity.

The robotic facade of the Al-Bahar Towers by Aedas Architects uses solar responsive dynamic shading screens, in the form of a ‘Mashrabiya’, that act as a secondary skin and control solar glare whilst optimising the use of natural light internally.

This brief overview illustrates various applications of mechanically reactive membranes. Even if there is almost no esthetic integration of the mechanic component, full and precise control of the reaction can be excerpted. The need for external energy input and deriving technological dependence are disadvantages.

- Naturally Reactive Membranes

This type of membranes generates motion based on the reaction of one or more components of the membrane itself. The design of the reaction is determined autonomously either according to the rules contained in the material, the design of the material or the organized combination of materials. The project HygroScope - Meteorosensitive Morphology by Achim Menges in collaboration with Steffen Reichert explores responsive architecture based on the combination of material inherent behaviour and computational morphogenesis. The dimensional instability of wood in relation to moisture content is employed to construct a climate responsive architectural morphology. Suspended within a humidity controlled glass case the model opens and closes in response to climate changes with no need for any technical equipment or energy.

The “Hydro-Fold” printer is the handiwork of Christophe Guberan, a third-year design student at the Ecole Cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL). He replaced the regular ink in the printer cartridge with an ink-andwater mixture, which, when printed onto paper in various patterns, creates fold lines. As the paper dries, it contorts and retracts along the damp areas, creating three-dimensional, sculptural objects.

The Smart Costumes research project explores the development of Smart Textiles and Wearable Technology for Pervasive Computing Environments. Heriot-Watt University’s Creativity Innovation and Design Theme funded the short speculative project. The aim is to explore the interfaces and interaction between smart textiles and smart – or pervasive – environments.

Naturally reactive membranes are ecosustainable, however up until today less controllable compared to mechanically reactive membranes.

4.Questions

The above illustrated applications of reactive membranes have hardly been translated into daily life. Only domotics deal with human necessities related to space. The use of digital technologies increases the quality of a building, partially automatically. However the achieved progress is mostly induced mechanically by men. Matter, as elementary unit of our lives, is currently not a consistent part of this process. Can the vibrational frequencies of our body affect our environment? How can we communicate with matter?